|

Guest Blogger: Anne Miller-Uueda, LCSW The aftermath of trauma is often isolating. There may be emotional, cognitive, physical, and behavioral changes that seem confusing. For folks who experienced trauma as a young child, these impacts are at times a part of life as far back as they can remember. Sometimes it can be hard to believe that others who have not experienced these effects can truly understand what you are experiencing as a survivor. Individual therapy is hugely impactful, if not vital, to help heal from trauma. However, having an individual therapist tell you that what you are experiencing is a normal reaction to trauma feels different than hearing another person describe an experience you recognize. This is one of the reasons that group therapy can be so impactful for survivors.

One of the best-known writers on group therapy is Irvin Yalom. He identified 11 curative factors in group therapy. All of these factors have a deep, resounding impact on trauma healing in the group setting. However, I want to focus on just 2 in this post: instillation of hope and universality. What is instillation of hope? It is the process of increasing belief that life can be better, or even good. This process is driven by watching the successes of other group members and having one’s own accomplishments recognized by the group. When you bear witness to the healing of others it can help you truly know that healing is possible. Universality is the concept that you are not alone in your suffering. Being in a group with other survivors normalizes your experiences and helps people to feel less alone. When isolation is a part of your daily existence, it can be monumental to be truly seen and heard by another person with a similar experience of walking through the world. So, at what point in the healing journey does it make sense to participate in group therapy? Groups can play a role at all points in the healing journey, but different types of groups work better at different stages of healing. Acute debriefing groups give opportunities to share experiences of trauma directly after the fact and are most often offered when a community has experienced some type of disaster that impacts many of its members. Support groups are generally time-limited, help survivors cope with the impacts of trauma, and begin to establish safety. Support groups can be found at many agencies in Philadelphia, such as WOAR Philadelphia’s Center Against Sexual Violence. There are also longer-term processing groups. These groups are most helpful later in the trauma healing journey when some baseline ability to handle anxiety and stress has been established. They can provide a space for members to reconnect to the here and now, reconnect to community, further understand and change the way trauma is carried within the self, and make meaning of the traumatic experiences.

4 Comments

Guest Blogger: Alisa Stamps, MSS, LCSW “Scorched Earth is a military strategy used by a people when the enemy is advancing on their territory. Anything of use to the enemy such as houses, food, vehicles, utilities or equipment is burnt, leaving nothing which could help the enemy sustain their assault” (Simon, 2016, p. 159). Boundaries. I feel like I talk about them with clients all day long. I say things like, “How would it feel to try and establish or even consider establishing better boundaries?”, or “Sounds like you put up a good boundary there for yourself”. They are so abstract and yet they aren’t. There are actual physical boundaries in this world—the Great Wall of China, the once existing Berlin Wall, and of course the soon-to-be-built, maybe-it-won’t-be-built border wall with Mexico. But what about personal boundaries? How do we build these? And most of all, how do we get the courage to build them and not see them as selfish, but rather self-helping? How many of you would say that you have a problem with boundaries? Let me dial it back…how many of you would say that you have a “problem with saying no”? I just posed this question to group members in the “Shattering the Mirror: Support and Recovery for Adult Children of Narcissists” group that I facilitate, and the answer was pretty much unanimous. In fact more than unanimous—there was noise and emphatic head nodding when this question was asked. In a relationship with a narcissist, the target is conditioned to learn how to not say “no”. Saying no may mean incurring wrath, so the target learns quickly that to preserve their safety it’s best to always agree or never challenge the narcissist. This agreement can then possibly spill over into other relationships in our lives. Romantic relationships or even work/boss relationships can be affected. We may work well past our eight-hour days or continue to take on project after project because we can’t say no. Conditioned targets can also be real people-pleasers. That might be part of why we can’t say no—we fear disappointing or losing our place as the “golden child” or “star employee”. The narcissist has made us believe that if we ever say no, we are less than or not good enough in their eyes. Someone recently shared with me the idea that boundaries can include both a door and a window. This idea was a game changer for me. I feel that when we are used to interacting with narcissists, because of their behaviors of idealization and devaluation, we are so used to things being black and white that the thought of considering some grey areas is foreign to us. JH Simon’s book, “How to Kill a Narcissist” states otherwise. It suggests that we can: “utilize the ability to say enough. We can remain in a situation but change the terms of engagement. We can go shopping with somebody but use some of that time to seek out our own stuff that we want. We can speak with a person then politely end the conversation when it gets too much. If the people in our lives love us, they will be flexible and open to negotiating each situation so that everyone is comfortable. We have the right to change the situation to suit our internal state better. When we do it in service of our true self, we never have to feel guilty”. (p. 157-158). See? Doors and windows. This takes practice. This is hard. Especially when we have not done much boundary setting before. But boundaries are scorched earth to a narcissist—they cannot continue their assault if their blood-source has been cut off, if the target is refusing to play the game. Start small with boundaries that don’t involve the narcissist yet by maybe not staying that extra hour at work, or not over-scheduling yourself during the weekend and see what that feels like. Pretty soon you will fall in love with “saying no” and hopefully also yourself along the way. Simon, J. H. (2016). How to kill a narcissist: debunking the myth of narcissism and recovering from narcissistic abuse. United States?: JH Simon. Guest Blogger: Alisa Stamps, MSS, LCSW Have you ever been in a situation where you just can’t seem to remember exactly how the events played out? Maybe you went out to eat with your partner and you remember having the fish, but your partner insists you had the chicken? And your partner does everything they can to convince you that you are not remembering things—what YOU ate--correctly? Sounds pretty harmless, right? Well, not when you involve a narcissist…

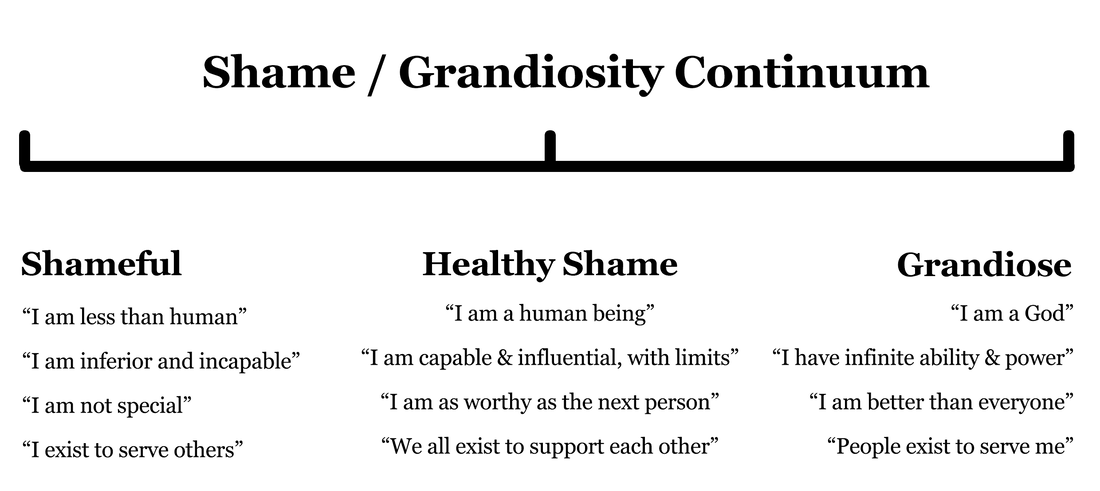

The Oxford Dictionary defines gaslighting as a “form of psychological manipulation where a person seeks to sow seeds of doubt in a targeted individual” (Oxford Dictionary). This is done to make that individual question their own perception, memory, and sanity in order to destabilize the target and delegitimize the target’s beliefs, using such methods as denial, contradiction, lying, and misdirection. The term originates from the 1938 play entitled Gaslight, in which a “husband attempts to convince his wife that she is insane by manipulating small elements of their home environment, including slowly dimming the gaslights in their house while pretending nothing has changed, thus making his wife doubt her own perceptions” (Angel Street). How does a narcissist utilize this skill to their target’s detriment? And how does this circle back to questions raised in my previous blog posts? Remember in my first blog when I asked who you see when you look in the mirror? Through gaslighting a narcissist is making sure that you see them—their thoughts, their perceptions, their beliefs. The trick is the make their targets think they are not capable of functioning without the narcissist, and thus the target will rely on the narcissist to give the “correct” version of reality. If we are “taught” that we can’t trust ourselves then we will inevitably be drawn to the person that has ensured their version of truth is the only option. Another tactic of gaslighting is known as “splitting” and one that the narcissist may use frequently. Splitting is when you are pitted against others by the narcissist, the purpose of which is to isolate you from the important people in your life. This can even happen in a clinical setting. In my previous job working as a therapist in an inpatient drug and alcohol facility, I would often have a patient that would tell me one thing and then go to another therapist to tell them something completely different or only a small version of the truth. In these instances, I would usually have to tell staff members to direct this patient back to me in order to put an end to the splitting. When the narcissist is challenged in this way and the splitting is disrupted, this tactic can usually be stopped or at least lessened. This type of behavioral monitoring is definitely not fun, but can be, if they are open and willing to take it in, a beneficial learning experience for the narcissist. But now back to the target. What can we do to help ourselves when gaslighting is present? Most importantly, make sure that you seek out your own support system: a therapist, a trusted friend or family member, a support group, etc. Second, hold on to what you know to be the truth. Try and stay grounded in your authentic self, and understand what it is that the narcissist is trying to do to you. Lastly, don’t be afraid to stop and pause before reacting. One of the best pieces of advice I heard early on in my career is that just because you were invited to the crisis does not mean that you have to go. Not reacting is a reaction and probably not one that the narcissist is used dealing with. Remember the shame/grandiosity continuum chart from my last blog post? Gaslighting is a tactic to inflict shame on the target and if we don’t bite, the narcissist can’t be successful. I thought it might be interesting to research TV or movie characters who have been crafted to use a gaslighting technique. One that was surprising to me, though I can totally see it now, was Ross Geller from Friends. Ross lies to Rachel about still being married after their ceremony in Vegas and convinces her that they are no longer married when in fact they are; he puts ideas in her head that just because he is the father of their baby she should be with him; and of course who could forget about the whole “We were on a break!” thing? Gaslighting at its finest. Until next time my friends (no pun intended), be like a tree and remain grounded. And please check out posted information for our new outpatient group “Shattering the Mirror: Support and Recovery for Adult Children of Narcissists” starting this next week. "Oxford Dictionary definition of 'gaslighting'". Oxford Dictionaries. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 23 September 2019. "Angel Street". Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved 23 September 2019. Guest Blogger: Emily Potter Cox, MA, LPC, CYT  Howard Stern shares why he avoided and then embraced therapy A LOT of people have reservations about going to therapy. What really happens when you sit and talk with someone, anyway? Does it work? Do they just want to take your money? It is not uncommon to have fears and reservations about starting or continuing with therapy, ESPECIALLY if you have seen a crappy therapist in the past. If you have---I’m so sorry. Like all professions, some of the practitioners are not as competent as others. BUT-- when you find that right person and you get that *click*, it is worth it! Have you been thinking about therapy for a few years? Perhaps you want to make some changes in your life, but are unsure if therapy is the right step? Your fears and hesitations are normal! If you have been thinking about therapy for a few years, perhaps you want to make some changes in your life but are not sure if therapy is the right step--your fears and hesitations are normal. Many people have hesitations and reservations about going to therapy. Here, Howard Stern shares what kept him from therapy, why he finally started it, and what he got out of it. Hint—He’s a fan.  I’ve listed TWO podcasts below. If you are generally offended by Howard Stern, I recommend his interview with Teri Gross in Fresh Air. You are least likely to be offended listening to that one. If you don’t find Howard Stern offensive, I recommend his interview with Conan O’Brien on the podcast Conan Needs a Friend. It is 3 hours long, but in between penis jokes, he talks about his experience in therapy. They discuss a number of themes, including depression, but if you want to skip to where they discuss therapy, it is around the 50:00 min mark. See the links to the podcasts below: Fresh Air with Teri Gross Interview with Howard: https://www.npr.org/2019/05/18/724044452/fresh-air-weekend-howard-stern-phoebe-waller-bridge Conan interview with Howard: https://www.earwolf.com/episode/howard-stern/ Guest Blogger: Alisa Stamps, MSS, LCSW In my last blog post, I mentioned that we would continue to address such questions as, “Are you wondering if you’ve been in a relationship with a narcissist?”; “What happens now that you’re aware of this”; and lastly, and maybe the most important question, “How do we get to the point where we can look in the mirror and see ourselves and not the narcissist?”. In order to begin to answer these questions we have to do it. We have to talk about shame. In my previous job working at an inpatient drug and alcohol facility, I used to give a lecture on the topic of shame. Usually when I announced this topic, I would get a collective “groan” from my audience. Why? Because shame feels icky. It’s uncomfortable and is not usually a place that we like to live for very long. JH Simon, author of How to Kill A Narcissist: Debunking the Myth of Narcissism and Recovering from Narcissistic Abuse, says that “shame at its mildest is a slight ache in the chest and at its most potent, it physically deflates you—you question yourself and hold back your opinions and feelings” (Simon, 2016, p. 28). In my lecture I used to ask my audience to describe what shame might taste like or feel like. The answers would run along the lines of shame tasting like “hot garbage” or feeling rough “like sandpaper”. These are not pleasant images. But to a narcissist, shame must be inflicted to the target or the whole thing doesn’t work. According to Simon (2016), shame “functions effectively two ways: -Personal: this kind of shame arises when the self does not meet a particular reality and comes up short. For example, not being able to afford the dream car that you’ve always wanted. -Social: this shame is based on the people and environment around you. For example, being given a disapproving stare by a loved one, or feeling like you don’t fit into a certain social group” (p. 29). In either situation, shame will come knocking at the door, reminding you that you need to improve or that you are not up to certain “standards” and then slam that door in your face. This is a narcissist’s dream come true. In order to maintain their states of grandiosity they must be able to count on their target’s shame. Simon (2016), explains that something that both shame and grandiosity have in common is that they require something and someone to measure against. That’s exactly how the narcissist/target relationship works in the shame/grandiosity continuum. (Simon, 2019) Obviously, healthy shame is what we are striving for. The next time you notice shame coming up, see if you can place it on the chart. Does it fall under healthy shame or are those feelings all the way to the left? Awareness is the first step toward change. But your awareness is not what happens in the narcissist/target relationship—the narcissist doesn’t expect it! If the narcissist continuously creates a scenario to make their target believe that they are small and beneath them, they have activated shame and the target begins to believe they are less than human. Reinforced continuously, and the target will stay there and that shame becomes part of the core identity. Tada! The narcissist has achieved their goal.

References Simon, J. (2016). How to kill a narcissist: Debunking the myth of narcissism and recovering from narcissistic abuse. Simon, J. H. (2019). Shame-grandiosity-continuum. Retrieved August 17, 2019, from http://www.howtokillanarcissist.com/how-to-kill-a-narcissist-book-sample/shame-grandiosity-continuum/ Written by: Kaycee Beglau, PsyD Whether it’s a friend, relative, or partner, we sometimes find ourselves with someone who suddenly begins to experience the acute effects of trauma. This typically presents as sudden fear or panic, flashbacks, intrusive negative thoughts related to the trauma, or dissociative states where the person appears to “not really be there” anymore. Of course, these experiences may be frightening, confusing, and overwhelming for the person experiencing them, and they may also be for the person witnessing them as well. If you are in a relationship with someone who frequently experiences these symptoms in your presence, it may be beneficial and empowering to have a sense of what might be helpful for the person in that situation. However, it is important to note that the purpose of this article is to highlight some quick and concrete strategies to help the person re-orient or “ground” during or after an acute trauma reaction, and it is not intended to imply that anyone in a personal relationship with another trauma survivor should take on the role of being an actual therapist. Think of the information in this article as a “first aid kit” for flashbacks – it’s to help you when you need it and should not be used in place of actual treatment from a trained professional. What to Look For:

What to Do: 1. DO NOT TOUCH someone (even a loved one) in an active flashback. This may be extremely triggering for them and the physical touch may inadvertently be experienced as part of the traumatic memory/flashback. As they are starting to come out of it and are becoming more oriented, it’s ok to ask permission to touch them (for example, placing a hand on their shoulder, a safe embrace, or using touch to guide the person to a better location). If they say “no” or appear to shutter or recoil, respect this as an indication the person does not want to be touched at that time. 2. Do not ask them to talk about the flashback details. It’s ok to ask if they are having a bad memory or if they feel like something bad is happening to them right now. It’s important to keep in mind that if a person is having a flashback, they are overwhelmed and flooded. This is not the time to try to get them to talk about anything related to the trauma. They need help coming back to the present moment, regulating their nervous system, and feeling safe again. 3. Orient to present time and surroundings. Identify yourself and announce where you are and say something present-oriented, such as your name and relation to the person, even if they know you well. Let them know where you are and remind them they are safe in the present moment. For example: “Laura, this is Sarah, your sister. You are here with me in your house in Florida. It’s May, 2019. It’s just me and you and nothing bad is happening to you right now. You’re safe here with me.” 4. Use a warm, but firm voice to give instructions.

Again, continue to use a warm, but firm voice consistently. The person may be relying on the presence of a supportive voice to “guide” them out of the flashback experience. You can continue to say things like:

Key Points to Keep in Mind:

Guest Blogger: Katie Fries, LCSW, RPT 1. Hold assumptions at the door It can be very easy (and understandable!) to assume that the struggles you faced in middle school are the same ones your child will experience: mean girls, peer pressure, opening lockers—you name it. And while some of those fears seem to stand the test of time (have they changed those dang padlock lockers?!), others will change based on both new forms of communication (like social media) as well as your child’s individual strengths and challenges. If we assume that children are concerned about peer pressure and talk with them all about how to “say no to drugs” when what they are actually concerned about is where they will sit at the lunch table, they may end up feeling unsupported and be less likely to disclose about the things that are actually stressing them out. A couple of helpful questions to ask are: “What are you most excited about?” and “What are you most nervous about?”. Asking those questions not only normalizes the feelings of excitement and nervousness, but it also gives them the opportunity to express what they need from you. That support may be similar or different from what was originally imagined. 2. Provide opportunities to practice Often the fears a child holds can be minimized by knowing what to expect. The fear of being late to class because they weren’t able to open their locker can be greatly decreased by becoming an expert at opening a padlock at home. The fear of getting lost in the hallways can be solved by walking from class to class before the first day of school. The fear of knowing how to say no to a party while saving face can be decreased by creating a plan or code word to use if they need you to assert that they’re not allowed to go out. While many schools offer the option of a tour for incoming students, if your child seems particularly anxious about starting somewhere new, it might be worth asking for a private tour of the space to assuage those fears. Again, it is important to attend to your child’s individual needs, as practicing or rehearsing something unnecessarily can unintentionally send the message that you doubt their ability to manage new situations. 3. Take care of yourself! Having a child transition to a new phase of life can bring up feelings of joy, grief, and uncertainty. Fears can easily arise such as: “Will my child be okay?” “Have I prepared them well enough?” and “What can I do to make sure my child doesn’t have to go through what I did?”. To avoid the trap of projecting anxiety onto your child, it’s a good idea to be curious about and validate any challenges during transitions that come up for you. This way you can accompany your child on their own journey in a way that’s healthy for them. Some of the challenges they will face will mirror your own, and some will be different. Knowing you believe in their capacity to manage stress and navigate this new time in life is the most effective way to help them have that same confidence in themselves! Guest Blogger: Alisa Stamps, MSS, LCSW  Who do you see when you look in the mirror? Do you see your smile, your shining eyes, the incredible qualities that you bring to your life? Or do you see the “bad” traits? Maybe even the traits that were projected there by someone else. That you are lazy, stupid, too heavy, or maybe even not good enough? How do you feel about the face looking back at you? Do you feel pride? Or do you feel full of shame? Who do you see when you look in that mirror? Is it you? Or is it someone else entirely? To answer these questions we must begin with the Greek myth of Narcissus. Narcissus was a hunter who was known for his beauty and love of all things beautiful. One day as he was walking in the woods a mountain nymph named Echo saw Narcissus and fell completely in love with him. Sensing he was being followed, Narcissus cried out, “Who’s there?” and Echo repeated, “Who’s there?” and tried to embrace him. Disgusted, Narcissus stepped away and asked her to leave him alone. Echo was heartbroken and spent the rest of her days alone until nothing but an echo sound remained of her. Nemesis, the goddess of revenge, caught wind of this story and decided to punish Narcissus. One hot summer’s day, after many hours of hunting, the goddess Nemesis lured Narcissus to a pool of water deep in the forest. As Narcissus bent to drink, he gazed upon his own reflection and saw himself staring back in the prime and bloom of his youth. However, he did not recognize it as his own reflection, and so he fell in love with it as if it were someone else. Narcissus was unable to tear himself away from his own gaze, and after some time realized that his love could not be reciprocated. He eventually withered away from the passion burning inside of him and thus turned into a gold and white flower. What does the myth of Narcissus have to do with what we know today as narcissism? The DSM V defines narcissism, or narcissistic personality, as a, “fixation with oneself and one’s physical appearance or public perception”. It also goes on to say that someone with narcissistic tendencies will have a need for admiration, will have a pervasive pattern of grandiosity, and will possess a lack of empathy. The terms manipulation and domination also come to mind when defining a narcissist. In order to succeed, the narcissist has to make the target (spouse, child, etc.) into an extension of themselves. This extension can pertain to both the emotional and the physical. The narcissist needs their target to believe that they are nothing without the approval of the narcissist. The narcissist will also, as is the case with many personality disorders, project parts of themself on to their target, and then attack those parts. Does any of this sound familiar? Are you wondering if you’ve been in a relationship with a narcissist in the past? Was that person your partner? Or maybe even your parent? What happens now that you’re aware of this? How do we get to the point when we can look in the mirror and see ourselves and not the narcissist? How do we recover from perhaps a lifetime of narcissistic, emotional abuse? Stay tuned as this and much more will be addressed in future blog posts. And be on the lookout for information about a new outpatient group starting in the fall, Shattering the Mirror—Support and Recovery for Adult Children of Narcissists. Written by: Kaycee Beglau, PsyD “Children are not meant to provide the emotional or psychological needs of parents.” – Sheila Darling In a “good enough” home environment, children have mostly consistent, predictable, and nurturing responsiveness from an attuned parent or caregiver. There is an internal experience of being taken care of that comes from healthy boundaries between the parent and the child. The child understands and knows on a deep level the adult is there and “has got this” while also not feeling overly controlled and smothered. There is a balance between dependence and independence, structure and freedom, love and discipline. In family environments that aren’t so ideal, as in cases where a parent experiences ongoing emotional difficulties, this balance is not achieved on a consistent basis. The child intuits, or “picks up,” that something is not emotionally (or sometimes physically) safe and takes on a sense of responsibility for taking care of the parent in a variety of ways, typically by providing emotional or physical caregiving to the disturbed parent. Life in this kind of dysfunctional family environment pulls the child into a role reversal with the disturbed parent. The result for the child is often a pervasive sense of worry or anxiety about the feelings and needs of the adult, feelings of depression or sadness, low self-esteem, withdrawal from developmentally appropriate activities and engagement with peers, and an exaggerated sense of being mature or “wise beyond your years” that equates with a lost childhood. Taking on these feelings and the overwhelming sense of responsibility for a parent is often referred to as being a “parentified child.” The costs to these children are tremendous. First, the child often learns that his or her needs are not wanted, acceptable, nor likely to be met. These needs are either ignored, neglected, or perhaps even worse, the child is actively punished, criticized, shamed, or rejected when expressing his or her own desires or wishes. As a result, the child learns how to “cut off,” bury, or deny his or her needs in order to take care of the parent’s and to prevent further disappointment or harm. Secondly, as an adult, there is often a deeply profound sense of shame that comes from having a personal need emerge. Throughout childhood, there was a complete orientation towards taking care of the parent, often at the exclusion of being aware of one’s own sense of self and healthy entitlement to personal needs and interpersonal boundaries. After growing up always being oriented toward “the other,” adults from this type of family environment often have a hard time developing certain abilities, such feeling entitled to saying “no” to others, expressing anger, getting close and developing deeper levels of intimacy, and feeling whole and worthwhile as an individual. If you recognize yourself in these descriptions, it is possible you grew up with a parent or caregiver that relied too heavily on you to meet his or her emotional and/or physical needs. Individual psychotherapy with a relational or attachment-focused approach can provide a certain kind of space and therapeutic relationship where you can be free to explore the effects of your unique childhood experiences on your development and ability to connect in healthy ways with others. Although this will inevitably require a certain amount of courage and willingness on your part, parentified children are undoubtedly strong and resilient by nature and healing and growth are certainly possible if given the right opportunity. Written by: Kaycee Beglau, PsyD  Traumatic experiences profoundly affect us in deeply personal ways, in part, because they make us feel out of control in this world, feel unsafe with others, and even unsafe with ourselves. We start to feel unsafe with ourselves, for example, when we question our own judgments, lose trust in ourselves, or carry a sense of inner badness, defectiveness, or self-disgust. We may find ourselves asking questions like, “Why did this happen to me?” or “What did I do to deserve this?” Sometimes, this inner sense of being to blame or of having some kind of inner “badness” is so significant, it makes us question or lose faith in our spiritual belief system. For example, we may say “I’m so awful, not even God could love me.” Inevitably, those who have experienced trauma find themselves trying to sit with and make sense of a tangled knot of intense emotions. These can include feeling anxious, frightened, alone, angry, sad, depressed, guilty, and ashamed. When these emotions are accompanied by thoughts of self-blame or self-hatred, it’s like pouring gasoline on a blazing fire. For example, when we are already feeling sad and alone, to think thoughts like, “It’s all my fault” or “I should have done something different” only makes us feel more depressed and isolated from others. So, in this way, a vicious cycle of negative, intense emotions and social isolation is perpetuated. Why is blaming oneself for traumatic experiences so common even though it can make us feel so much worse? To outsiders, it may seem obvious it is not our fault or even absurd that these kinds of thoughts could be believable to us. But, the truth is, there are many understandable reasons why we can tend to blame ourselves. These reasons often center around themes of either 1) Needing to have a sense of control or 2) Needing to have a sense of meaning. Following is a list of some examples of underlying (or unconscious) reasons why we can hold on to self-blame after traumatic experiences:

With this being said, it makes perfect sense to me why some end up carrying around this sense of self-blame despite how much worse it can make things feel. On the other hand, it has been my experience that those who carry these feelings around the most are also the ones who carry a tremendous amount of shame and who are the most likely to be suffering from other serious symptoms of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). This may be because the shame is so powerfully painful, it can keep us from talking about or coping with the traumatic experiences in ways that could ultimately be healing and freeing. The shame keeps us wanting to avoid the trauma-based thoughts, feelings, and memories and from sharing these with potentially helpful others because it can be so frightening and painful. However, the avoidance only ends up keeping us trapped inside ourselves, without being able to get the support needed to face, process, and ultimately resolve the feelings of shame or guilt and to heal from the traumatic experiences themselves. If you find yourself relating to these experiences of self-blame, I encourage you to find someone you can trust (even just a little bit at first), whether that is a friend, a relative, a spiritual or religious leader, or a licensed therapist and start to take the healthy risk of sharing your story with someone. Its going to feel very scary and painful at first, but over time, having someone hear your story and accept it without judgement can help you start to resolve these feelings of shame, self-blame, and self-hatred and to move forward in your life. |

|

We are a full-service private practice offering a variety of therapeutic services conveniently located in Old City, Philadelphia.

|

Important Links

Blog

|

GET IN TOUCH |

Copyright © 2018 Turning Leaf Therapy LLC All Rights Reserved.